Written by: Jackie Mora

A 6-year-old girl born in Cambodia could never have predicted the atrocities of a brutal guerrilla warfare group who stole her human rights, massacred millions and forced her and her loved ones to endure to survive as their country was being destroyed.

That young girl was Sotheary Ortego, Riverside City College alumna and author of “Soulful Journey: Against All Odds.” The book is inspired by the courage of her family and other families devastated by the effects of communism and genocide in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge reign from 1975 to 1979.

“You don’t belong to your family, you belong to the government,” said Ortego to portray the extreme disregard for human life and rights the Khmer Rouge held as truth.

Ortego’s life story boasts the bravery and tenacity it took her and her family to live through the terrors during the takeover, yet she humbly depicted what was once her reality.

She began by humorously thanking the crowd for taking the time to attend even though it was around lunch time and everyone was probably hungry. Her friends, family and mentor were among those who experienced the incredible retelling of her history.

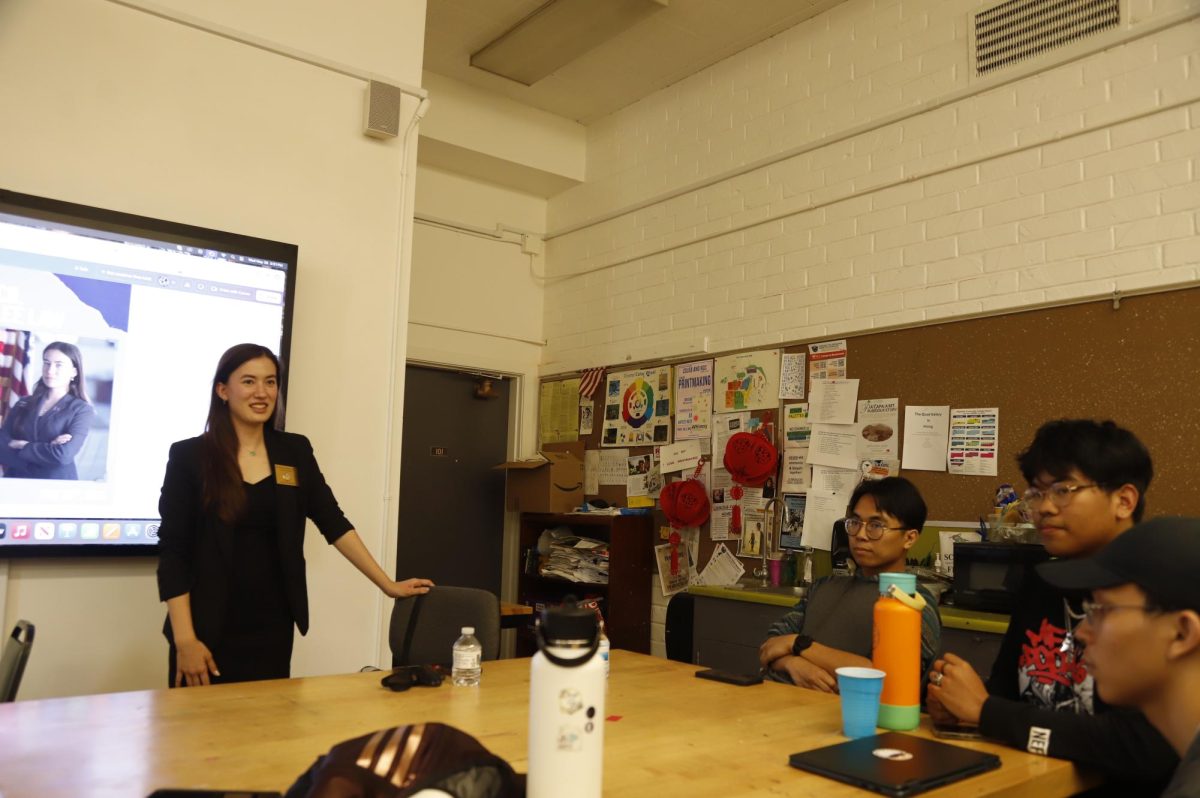

“What makes humans so resilient is despite all of the things that happen in the world we have many things going on but we still can be here,” she said in her lecture delivered Sept. 22 at the RCC Digital Library 121.

The event was organized by Estrella Romero, associate professor of communication studies, as part of RCC’s Discovery Lecture Series.

Ortego shared that the theme of these lectures is to help people create and that is why she came to share her remarkable life story and her ambitious creative process in writing the novel.

“I didn’t know much about my own history because back then we weren’t allowed to go to school,” said Ortego.

Adults were separated far away from the children and sent to work in the fields.

Ortego and her family held on to hope to get through these horrible conditions. “We just wanted to live from day to day,” said Ortego. “For me I think it was my baby brother, I had to live for him.”

“Very few babies survived during that time,” Ortego said. To help keep her baby brother alive, she would sneak out at night to the nearby communal children’s camp where he was kept.

Intellectuals were targeted and murdered to keep the population uneducated and unquestioning.

“They killed educators, doctors, lawyers; they killed anyone they thought might rebel against the government,” said Ortego.

Ortego’s family was sentenced to execution because both of her parents were teachers.

On the day of execution, they were scheduled to be murdered at 3 p.m., but for an unknown reason the killings were stopped at 1 p.m. This was not the first, but the second time the family was saved from execution by an abrupt unexplainable reason. The third time only her parents were taken to be killed, yet again were released for reasons unknown.

The family was then displaced and separated from each other and put into labor camps once more.

The Vietnamese invaded Cambodia in January of 1979, which erupted a war that indeliberately saved the family from the camps under Khmer Rouge rule.

“When the Vietnamese were in the country they only allowed us to do collective farming,” said Ortego.

This meant the government controlled what was planted and took an unequal amount of the harvest for themselves.

“We couldn’t make enough rice and corn to support the whole family so after that we were starving,” said Ortego.

Her mother realized that there was no future for the children and decided it was time to go. As one of the few surviving teachers left after the war, Ortego’s father did not want to abandon the people. Her mother gave him an ultimatum and he decided to join the family on their dangerous quest for a chance at a decent life.

The family escaped the aftermath of the war-torn country on foot and headed to the border to Thailand. During this trek, Ortego carried her baby brother on her back.

They witnessed Thai soldiers robbing and shooting people along the border. A terrified cousin of Ortego had given the baby sleeping pills to prevent him from crying in hopes of keeping them out of harm’s way. Her brother nearly died.

The family made it across the border to Thailand. Ortego is grateful to the UNICEF volunteers at the refugee camp who helped revive her brother and save his life.

Ortego’s baby brother, as she called him, is Veasna Chiek, associate professor of mathematics here at RCC. Ortego shared that her brother’s name translates in English to mean “lucky.”

After surviving the war, the camps and multiple near death experiences, the family made the move to the United States and arrived in Riverside, California during 1982.

Denial of their human rights, which includes the right to be educated and to educate others, only intensified the family’s desire for this fundamental truth.

While Ortego was in high school, her mother was attending classes at RCC to earn her associate degree in Cosmetology to help support the family. Her mother, not wanting to walk the campus alone at night for safety reasons, suggested Ortego start taking night classes also so they could walk together.

The campus offered high school students with a GPA of 3.5 or higher the opportunity to enroll in classes.

Since Ortego excelled academically, she agreed to join her mother in getting a college education.

Ortego continued taking classes at RCC until she graduated high school. She proceeded to the University of Southern California, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in Nursing. She is currently a registered nurse at Kaiser Permanente Riverside Medical Center.

“For whatever odd reason, we’ve been saved so many times,” said Ortego at the lecture. “And that’s why I’m here today.”

“If we don’t care, we go from day to day just focusing on our own needs … I think sometimes we lose touch with humanity.” Ortego said.

“When we lose touch with humanity, we lose touch with part of ourselves. I think that’s why genocide or holocaust happens because sometimes we stop caring for one another, we stop loving one another, and we stop showing compassion for one another.” said Ortego. “A story like this is not to blame people but to show people what happened, so we can learn from it.”

When she began writing she didn’t know what she wanted to create. She always enjoyed movies so she decided to draft a screenplay.

Her first screenplay was a horror story because she learned that this genre was cheap to produce and easy write. “I didn’t have the inspiration behind the story,” said Ortego. “But I had a goal to finish, so I crafted the whole screenplay in 6 months.”

“I sent it out and got a few responses back, but I just knew it wasn’t a good story and I didn’t like it myself,” Ortego said laughing in retrospect.

The plot was about a psychopathic drug addicted patient who was angry at a doctor who didn’t prescribe him his medications. The psychopathic character killed all of that doctor’s patients and framed the doctor for the crimes.

“When I was writing it I thought I liked it,” said a smiling Ortego. “I don’t know where it’s at now, maybe under my bed somewhere.”

She moved on to write a second screenplay called, “Blind Faith,” which had the beginnings of what she would later craft into “Soulful Journey”.

Upon sending it out to Hollywood for feedback, she was told that movies weren’t being made about “boat people” but about comic book heroes.

She also received the constructive criticism that her writing was too beautiful for a screenplay and that she should try writing something different.

Ortego wrote a short story and she continued reworking and rewriting her ideas.

Though she felt intimidated she was encouraged by others to keep growing her story. She didn’t think she had the skills to pull it off, but was determined to give it a try.

Her writing was reviewed by one of her mother’s clients, who was an editor for the Los Angeles Times. The editor invited Ortego to join a writers group that he was a part of. Ortego felt intimidated by her lack of experience and she didn’t think she was capable of completing the story.

“I found out we learn from each other, we all have something to contribute,” said Ortego.

“You have the seed inside of you, but you have to take it out, plant it, water it, nurture it and let it grow,” Ortego said. “It’s not going to grow if you don’t work on it.”

“Soulful Journey” is a rare and significant piece of historical fiction. Many of those who experienced the reign of terror in Cambodia firsthand weren’t allowed education or didn’t survive, therefore their story is silenced.

It is based on the oral history that is passed down from generation to generation. It is inspired by the life of a woman from a small Cambodian tribe who has survived many generations of conquerors and wars.

Ortego has incorporated her own war survival experiences with the oral histories of other survivors. The novel represents that fairly seen perspective of the people who suffered in the countryside.

“Only you know what your purpose is, nobody can tell you,” said Ortego, sharing her advice to aspiring writers and creators.

She emphasizes the importance of thinking about one’s future. “Sometimes we get too busy … we get lost in this world and we don’t realize our purpose,” said Ortego.

“People are afraid to admit that they have failed, that’s one of the obstacles that keeps some from inventing anything,” Ortego said.

Having a humble disposition and being truly open minded are characteristics that have helped Ortego to succeed.

“We have to look at and listen and allow ourselves to be corrected. Allow ourselves to be instructed,” Ortego said.

She discussed her apprehension in doing the lecture. “I was nervous and scared,” said Ortego “I’m half deaf and sometimes when people talk to me, I can’t hear them or understand them.”

Despite her fears she accepted the challenge. “The best thing to do would be to hide in my comfort zone and not do it right? But it was an honor to do it, you see, that’s the difference there, so I made up my mind to do it.”