By Diego Lomeli

There’s always been a superficial side to documenting people, and with that comes the hollowed-out questions that we expect to read about.

When interviewing an artist, the unavoidable question must be thrown into the mix: “What does art mean to you?”

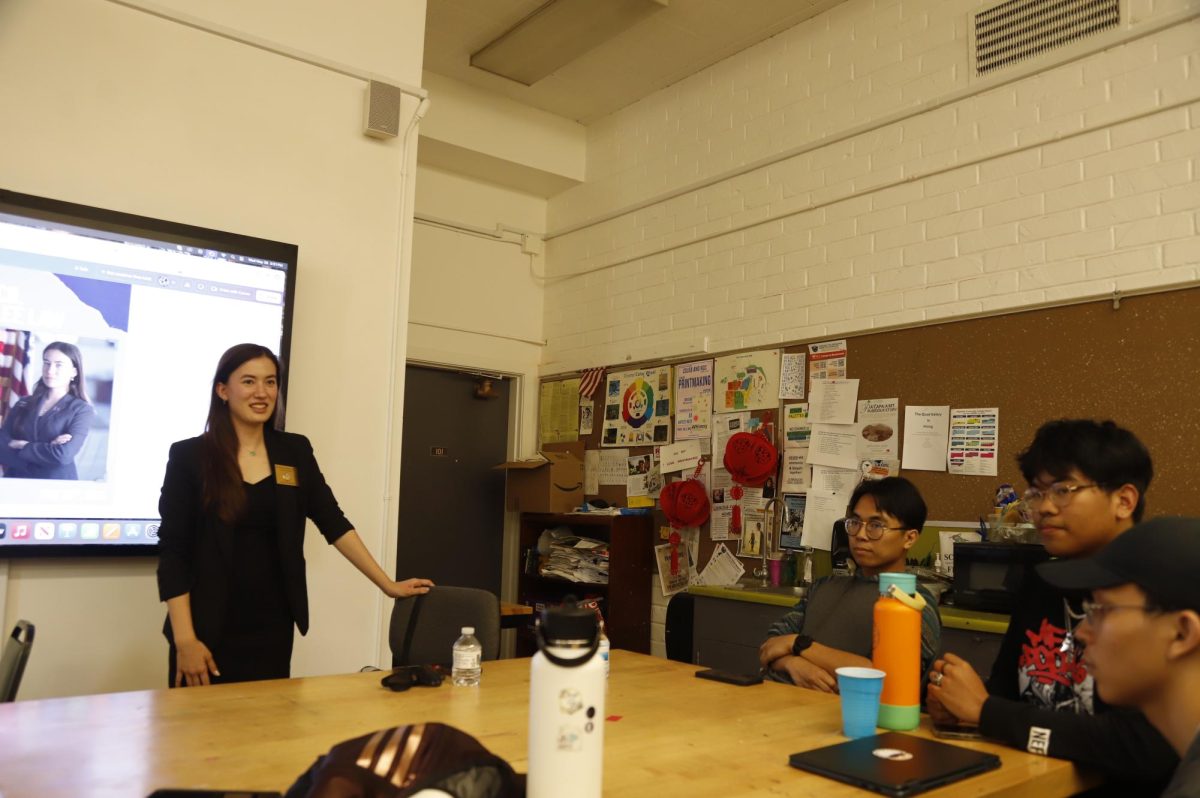

To Xonasuchi, interviews like that are on par with flimsy throwaways — something that’s not meant to hold attention for very long.

“It’s kind of like humans. Once you grab something and obtain it you’re like OK, got it— let’s go to the next one,” he said. “That’s why I don’t like interviews. I like to be anonymous and private. People don’t even know much about what I’ve done and I think that’s so cool.”

Xonasuchi once told himself that if Jay-Z was the only one looking at his photos, he wouldn’t need anyone else. The audience that he has managed to build up is small, but it’s important to him.

Like a lot of good art, it all began as an effort to impress a girl. After it all fell apart, a heartbroken Xonasuchi began photographing simple things: wet rocks, trees, puddles and clouds with a camera he bought. From there, his photographs began shifting into something a lot more abstract.

“I treated it like art therapy,” he said. “It went from forgetting this girl to, ‘my thoughts have been weird since I was a kid, why don’t I just express them through this visual medium?’ So I just began coming up with ideas and shooting them.”

Most of his work is on his social media page, but only for a short while, as he is prone to removing his posts after he moves on to newer, fresher ideas.

“I don’t know why I remove it,” he said. “Maybe it’s so it seems special to what you’re looking at now. To me personally, now it’s off the shelves and I think it creates this scarcity factor.”

Instead of an online portfolio, Xonasuchi referred to his social media page as if it were a tangible place. “The digital world,” he called it. As an artist aiming to produce a livable income through his art, more contemporary means of interchanging cash and art obviously stand more appealing than traditional online stores or brick-and-mortar studios.

Things such as NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) promise a good opportunity for Xonasuchi and his vision.

“Since February I’ve been looking at NFTs, and I stumbled across this blockchain that’s green, carbon negative and easy to use,” Xonasuchi said. “From there I met this French developer, and we’ve been going back and forth on this concept of tying in a physical work of art to have software and to have a use for it.”

This concept would work as a pass-around counter that pays out as a buyer’s fee or a tax. It makes sense to think of it as a dividend that only pays when the artwork is bought and sold. One transaction would equal one payment directly into the artist’s pocket.

Like NFTs, each artwork would be binded to its unique digital signature and would be impossible to replicate or produce fakes. Each piece would also be a part of a collection and individually numbered or identified. The value of each collection would be based on the sole popularity and reputation of the artist themselves, the rarity of the collection and other external factors such as pop-culture trends.

With all of it in mind, Xonasuchi’s concept poses the question: will the ownership of rare digital art pieces eventually rival or surpass the perception of incredible wealth?

“Maybe wealth might still exist, but it’s going to be more of a construct than money already is,” Xonasuchi said. “It’s obviously not going to exist, it’s just going to be a counter on a screen. In the grand scheme of things it doesn’t really mean anything, it all boils down to how we perceive wealth.”