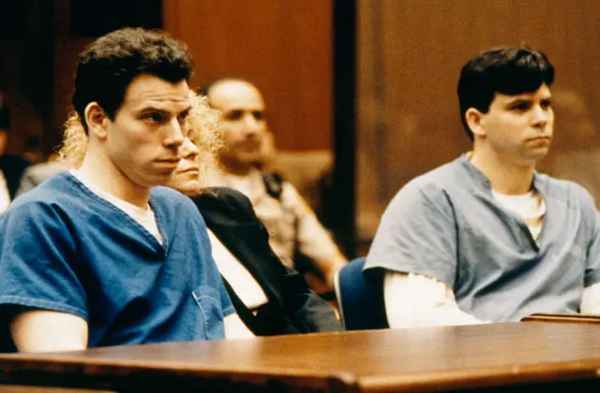

Ecologist Taylor Zagelbaum sits at her desk in her mobile office in Riverside County’s Hidden Valley Wildlife Area. She is surrounded by posters of animals and insects, and behind her a fish tank bubbles.

Zagelbaum works as a Natural Resource Specialist for Riverside County. She monitors native plant and animal species and restores natural habitats after wildfires.

“Southern California,” she beamed, “is a biodiversity hotspot. We have all these different species that reside here. It’s so wonderful.”

In California, where the rate of wildfires is growing, ecologists play an important role in rebuilding natural habitats after they have been affected by these fires.

These wildfires have a significant impact on local wildlife. “The scale (of fires) has increased,” Zagelbaum says. “There is an onslaught in terms of one fire after another.”

“We are working with BLM, the Bureau of Land Management. Their properties, which are adjacent to ours, have burned as well.”

“We’re tag teaming on restoration tactics. We make a fire line so if this area burns, we will save this (other) area.”

Many species try to escape from the fires to adjacent areas, but some like the Quino checkerspot butterfly, are unable to.

“It’s going to be the end of the species as we know it,” Zagelbaum said “We’ll see with early surveys next year. I’m working on the restoration action plan for that specific fire to try to rebuild some of that habitat.” She believes the species may produce hybrids that will be more resilient towards fires.

Working directly with plants and animals is a dream for many biology students, but it is not an easy profession to break into. Zagelbaum offers her experience in the biological field and advice for students who hope to one day conserve habitats for native wildlife.

When asked how biology students at RCC can best prepare themselves for a career, Zagelbaum said, “There’s no better experience than doing internships. I wish I had done more internships earlier. I did restoration work with the Palos Verdes Peninsula, habitat restoration, invasive removal.”

“Volunteer early,” she said, suggesting that students might cold-email for volunteer opportunities through groups like Audubon National Bird Society and California Bat Working Group.

Zagelbaum shed light on the realities of being a female ecologist in the scientific field. “It’s still a challenge. Sometimes you’re undermined just being a female,” Zagelbaum said.

While getting her master’s degree, Zagelbaum experienced misogyny from one of her advisers. However, in recent times she has had a more positive outlook on the field. “I think it’s getting better with more women in the field. My boss now, he’s amazing.”

When entering the biological field, Zagelbaum encourages students to have realistic expectations. “Doing what you want is not always glamorous,” she said. “When I was consulting, I would go out to the freeway underpass to check for desert tortoises. It was not a great area, the 210 underpass. Bodies were found there. It’s not always working with the coolest species in the coolest areas.”

Even with her master’s degree, breaking into her chosen field was not an easy task for Zagelbaum. She said, “I have been told not a lot. I have been rejected a lot. Eventually, you are gonna have somebody say yes. Getting into the field was so hard. You have to give a lot of your time. You’re paid by your experience. It’s also who you know. There’s a competitive dynamic.”

When biology transfer students are choosing their schools, Zagelbaum says to research your professors. “If you’re interested in mammalogy, do they have a mammalogist? The professors get all the connections. That’s such a wonderful resource.”

Zagelbaum advised concerned Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) students. “There’s a light at the end of the tunnel. You will get through it. It’s so minor in the scheme of things. No one’s ever asked for my transcripts. They asked for a paper that said I graduated. You got this.”