By Erik Galicia

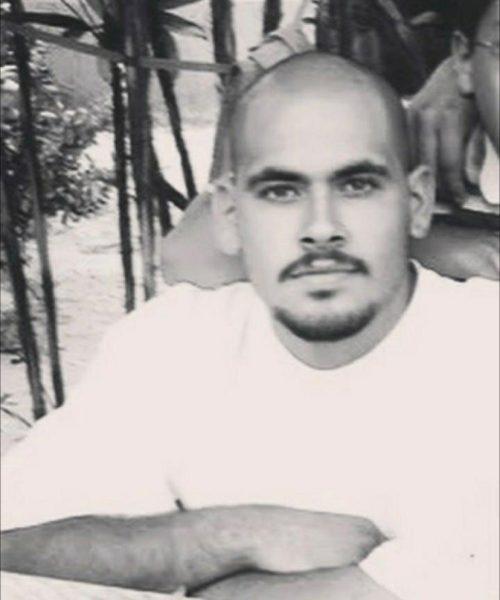

Ernie Serrano died like countless others have in police custody.

He stopped breathing Dec. 15 in a Rubidoux Stater Bros. after a lengthy struggle with Riverside County Sheriff’s deputies. But to the Serrano Family, he was more than the man who gasped his final breaths at 33 years old on a market checkout counter.

Ernie was a published poet who spoke out against injustice. The Serranos said he touched every household he stepped foot in. He was like a son to his aunts and uncles, and like a brother to his cousins.

He was born on July 13, 1987 to Teodoro Serrano and Maria Lowrie, a young Los Angeles couple who the Serranos described as madly in love. But Teodoro, at just 19 years old, was murdered during Lowrie’s pregnancy.

Teodoro’s youngest sister Sandra Serrano was 8 years old when Ernie was born. But even as a child, she said her maternal instinct was sparked by her nephew’s arrival.

“I thought about all the love and patience my brother had with me growing up and how I wanted to provide the same for his son,” she said. “A couple of days later he came home from the hospital with his mom. I remember holding him and he was just so tiny.”

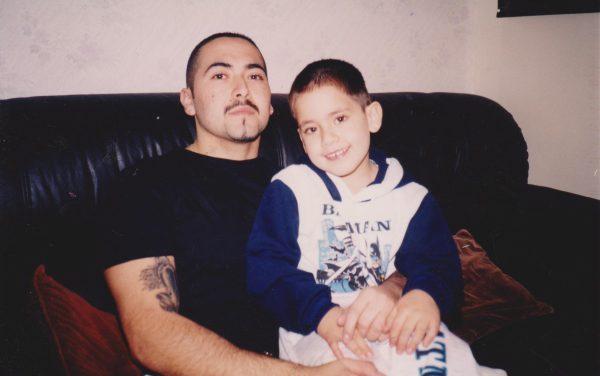

Ernie’s formative years were unstable. He bounced around between his mother, aunts and uncles. Sandra played both the role of his mother and big sister. Her daughter Natalia Serrano looked up to Ernie as her older brother.

Shortly before Ernie’s death, the three lit the fire pit in Sandra’s backyard, drinking homemade micheladas and chatting as they always had: playfully but with honesty.

They stayed up late, Ernie telling Sandra which of her ex-boyfriends he liked and didn’t like. They didn’t take the jokes to heart. It was how they bonded.

“That was our relationship,” Sandra said. “We were just so honest and upfront with each other, and we always knew it came with love. That’s something I’ll never be able to experience with another person.”

Ernie’s relationship with each Serrano was special.

To Natalia, he was the annoying older brother she traded wisecracks with. She also called him her artistic inspiration.

His pain bled profusely from his pen. Through his writing, he communicated the struggles of growing up without a father and the inequities he perceived in the world. He wrote socially conscious bars, dreaming of one day making it as a rapper. His dream was not for fame and fortune but for the ability to address social issues on a large platform, Natalia said.

According to his uncle Serafin Serrano, Ernie dreamed of alleviating suffering.

Serafin recalled Ernie studying Aztec and Mayan history, focusing on the smallpox epidemic created by European settlers during the Americas’ invasion. He challenged the establishment even as a grade-school child, turning in an essay entitled “Christopher Columbus was a Savage.”

Natalia turned to Ernie for help in writing poetry when she was in sixth grade. She didn’t know how to release her creativity, but she knew Ernie did.

“He gave me a creative key,” Natalia said. “He told me, ‘Every word doesn’t have to rhyme. It comes from your heart.’ That was something really big. I didn’t realize it at the moment.”

Natalia became immersed in writing as a teenager and began drawing as an adult. Ernie told her how proud he was of her paintings and drawings shortly before he died.

“I told him, ‘You were the one who taught me how to be creative,’” she said. “That was such an amazing gift that he gave me. All my other family members who have passed away, they were artists. I feel like that was him passing it to me.”

Air Force Staff Sgt. Alina Serrano, Serafin’s daughter, received the same gift from Ernie. Serafin raised them together when Alina was in elementary school and Ernie was in middle school. Having five sisters, Ernie was the brother she never had.

They spent their time watching “The Simpsons” and “South Park,” and movies about aliens. He enjoyed discussing extraterrestrial conspiracy theories with Alina, as he did with Natalia. She would take his action figures to pair up with her Barbie dolls, often getting on his last nerve, she said.

But Alina’s best memories of Ernie are musical. She recalled listening to Immortal Technique’s “Dancing with the Devil” for the first time with Ernie, a moment that is imprinted in her memory.

Ernie didn’t playfully tease Alina like he would his other cousins. Although he would do everything in his power to make her smile, she said he mentored her more seriously.

Alina described herself as being a loud and expressive child who was perceived as weird by her peers. Ernie taught her there was nothing wrong with that.

“He reminded me that it’s OK to be yourself,” she said. “He taught me that the world isn’t black and white. He introduced me into questioning the world. He exposed realities to me.”

Serafin’s relationship with Ernie was significantly different from the rest of the Serranos. Ernie’s father Teodoro was not just Serafin’s older brother, but also played the role of his mother and father. Teodoro’s murder sent a young Serafin on a destructive path, ultimately landing him a five-year incarceration.

Ernie visited him during that time, and they continued seeing each other when Serafin was released. By the time he was able to take his nephew in, Serafin had channeled Teodoro in order to provide the same warmth and safety Teodoro had once given him.

“His father is right here,” Serafin said, sitting in the Corona graveyard that allows him a place of peace and reflection. “This is his father.”

He tried his best, but the situation was not easy. Although created from immense love between his parents, Serafin said Ernie was also born to the shattering grief his mother experienced after Teodoro’s murder.

The Serranos talked about Teodoro often, telling Ernie how beloved his father was and how he had inherited that adoration. Serafin and Sandra referred to Ernie as what they had left on this Earth of their loving older brother. Still, Ernie felt a disconnect.

Alina, stationed in Hawaii, said her physical distance has allowed her to tune out from expressing her grief, partially. She felt as if she grieved for Ernie before, when she realized his struggles were overtaking him. She expressed regret, though the circumstances were out of her control.

“I wish our family was capable of providing more,” Alina said, tears creeping down her cheeks. “Our family did the best they could. But being passed around, he took that in and felt like ‘no one wants me.’”

One of Ernie’s poems was entitled “Nomad,” a description Serafin said fits his nephew well. He did not only shift between households but between light and dark. As an adult, his battle with meth resulted in periodic jail stints and drifting in the streets.

As a father figure, Serafin had to make the difficult decision of denying Ernie entry into his home from time to time. The last time Ernie was released, he showed up at Serafin’s door with the healthy glow often seen in a hopeful, recently released man. He remembered the love he saw in Ernie’s eyes.

But Ernie was released to a family in strife, Serafin said, and relapse came shortly after. No amount of meth or alcohol was enough to soothe the pain and trauma that gripped his nephew’s heart.

Still, Ernie was a gentle man, he added.

“I know violence,” Serafin said. “He came from a lineage of violence, but he himself was not violent. Aside from the typical playbook of resisting arrest he must have on his record, I know his temperament. It was not a violent one, rather, a very forgiving one.”

The Serranos have spent the months since Ernie’s death rallying for justice. Serafin, though, has refrained from verbally attacking the police in honor of Ernie’s heart-oriented temperament.

“I’m committed to do whatever I can to love, nurture, support, encourage and cultivate other loving individuals,” he said. “So if they go into law enforcement, they have the spiritual and mechanical wherewithal to treat people with dignity.”

The Serranos are focussed on highlighting the importance of difficult conversations about mental health and how people cope with their pain. The removal of the stigma, they said, is long overdue.

To the Serranos, justice for Ernie will go far beyond a court decision facing the deputies that responded to the call Dec. 15. They have met with other families of victims of police violence. They have been there for each other.

To them, it will be a lifelong fight.

Merry Alligood • Mar 11, 2021 at 9:06 pm

I am sorry for the tremendous loss your family is enduring and pray that it will soon evolve into rejoice for the memories and love he gave to you in life. I hope that the pain of losing him will not linger long, so that the joy of having him prevails over it quickly. God, who is the only rightful giver and taker of life, is kind and loving, even when we may not be able to see it. And all things are exactly how they must be, and in our best interest, truely. Lean on God and trust him, and remember Teddy and the love in his heart. And joyfully cherish that . May God bless you all.

Jeremy Sennett • Mar 11, 2021 at 8:46 pm

Will you please share the full and detailed story as to why he was detained and struggled before death by the police? Thank you.