By Samuel James Finch | Staff Writer

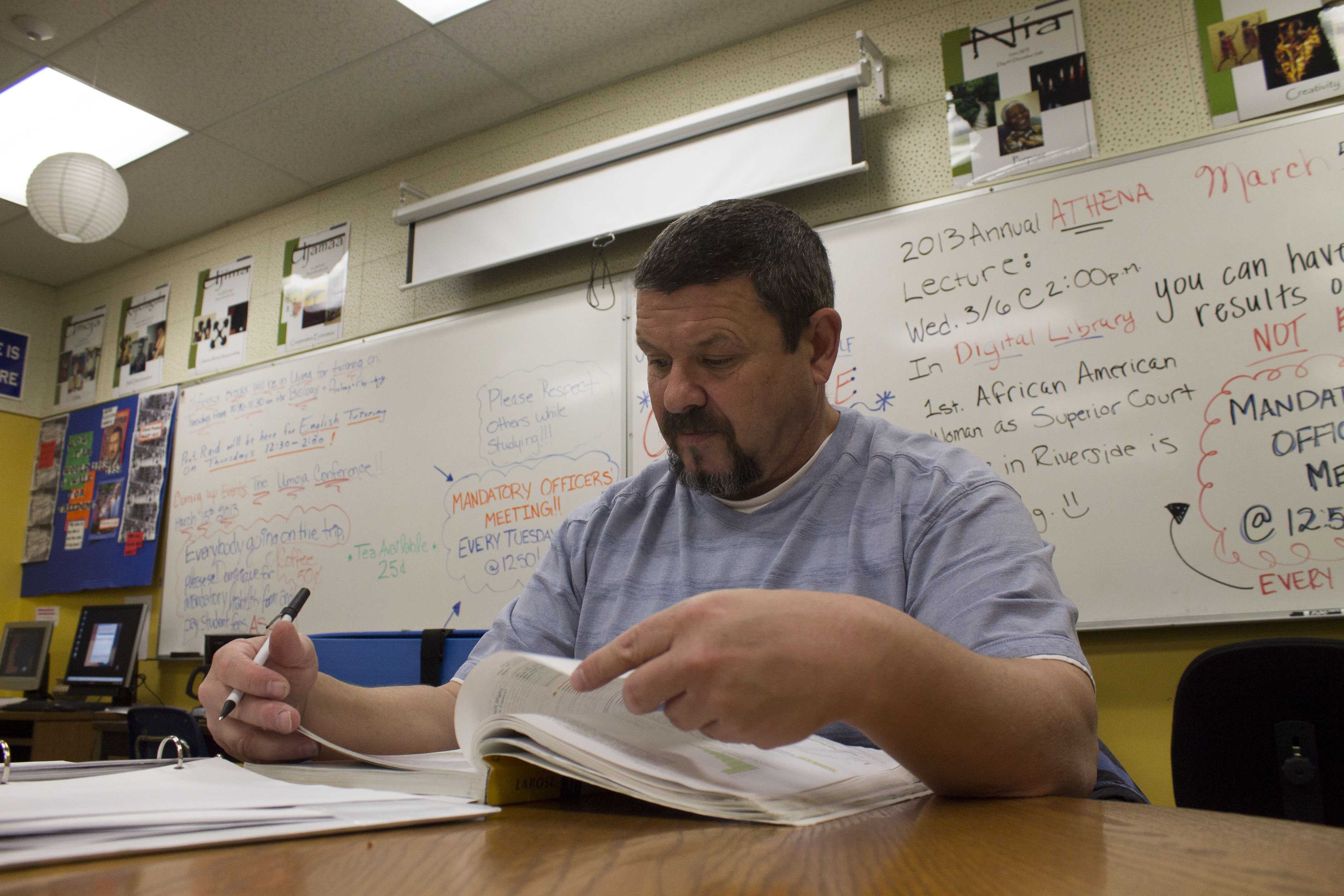

For Paul Jones, graduating from Riverside City College in May with conditional acceptance to Cal State San Bernardino is a light at the end of a long, winding tunnel.

Jones, now 51, had a troubled start in Akron, Ohio.

Born into a dysfunctional household, he suffered abuse and neglect, the toll of which drove him to first experiment with alcohol at the age of 11.

After struggling to graduate high school, Jones enlisted in the Navy at the age of 17 to leave Ohio behind, relocating to California.

His two years in the service, however, did not help his budding alcoholism.

“Drinking and going to other countries is a right of passage, so it was an excuse to drink,” Jones said. “It wasn’t frowned upon – it was encouraged.”

When he was discharged in 1982, Jones decided to remain in California, despite not knowing anyone in the area.

“I’ve never wrote home, I’ve never called home,” he said. “I know nothing about my immediate family … I don’t know who’s alive and who’s deceased.”

Homeless in Los Angeles, Jones’ drinking and ongoing battles with severe depression and PTSD worsened.

This cycle eventually led to intravenous drug use. His involvement with methamphetamine soon put him on the radar of law enforcement.

Jones first went to prison in 1990, returning on additional drug charges over the following two decades.

Out on parole, Jones found himself dissatisfied.

“I knew there had to be a better way. Yet I knew I didn’t have any tools to get to a better place.”

In 2000, Jones was handed the first of the tools he needed.

“I was on the bus and I saw Rio Hondo Community College and, for some reason, a power greater than myself got me to push the button and walk up the hill,” he said.

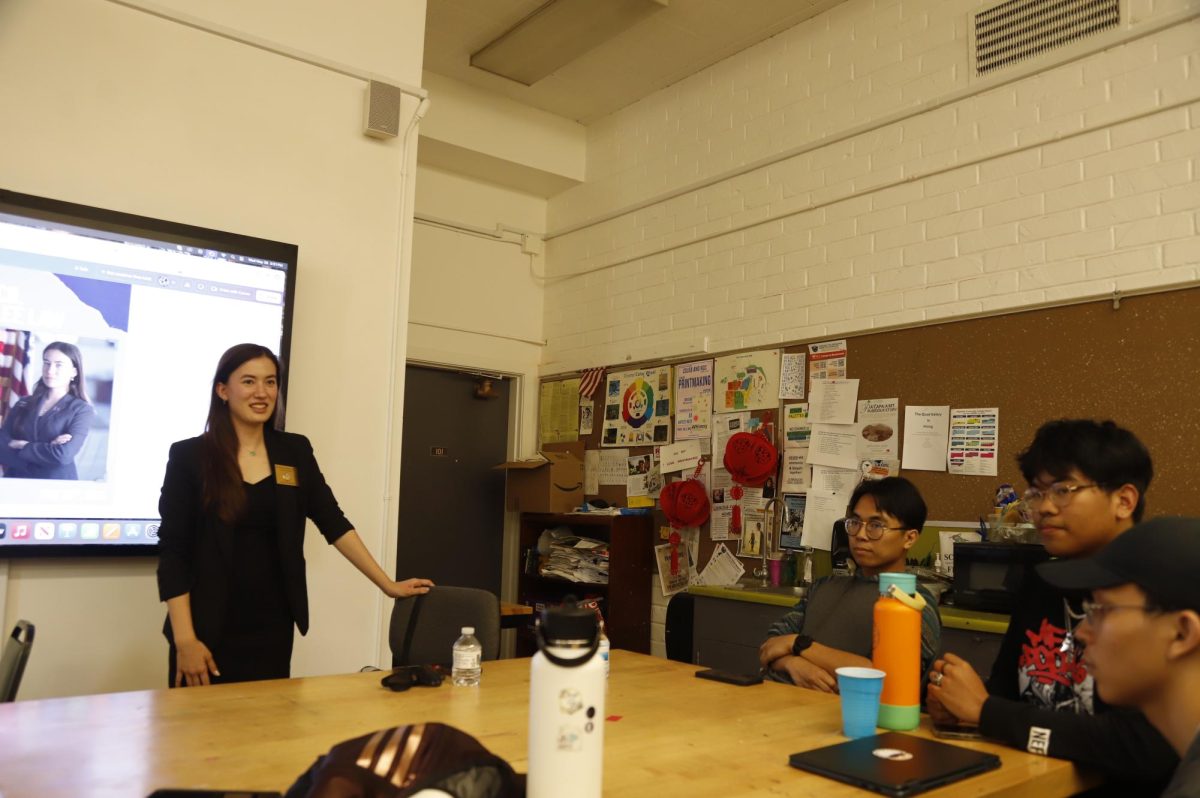

Luis Solis / Photo Editor

Jones enrolled and excelled, earning several certificates and being named Drug Studies student of the year.

This first stroll within the halls of academia filled his nostrils with the scent of something greater.

But once again, life took over and Jones ended up back in prison.

The time away from school gave Jones an opportunity to reflect on his intentions.

“The whole thing for me when I started college was a way to obtain money semi-legally,” he said. “When you look at it from a sociological standpoint, it was functional because I was going to college, but innovative because I was doing it for the wrong reasons. I excelled, but I wasn’t done with the life I lived.”

The life he lived had become his reality, the subculture of shopping carts and bridges.

“It’s the only thing I know,” Jones said. “I know nothing else. I have kids I don’t know, I’ve got a granddaughter I’ve only seen one time. Now my youngest daughter, who was born with muscular dystrophy, kind of encouraged me along, to get back into school.”

His youngest daughter, Gabriella, has served as a wellspring of motivation.

All the while Jones has slept in cars, staying with friends when possible.

“She didn’t ask to be born with muscular dystrophy and she deserves the best life that she can get,” he continued. “And in order for her to have that, I need to become somebody, to give her something.”

Though his paternal aspirations to better Gabriella’s life began early, Jones’ personal struggles prompted Child Protective Services to intervene.

“A social worker showed me a better way of life.”

Jones then gathered his transcripts and discovered that he was classes away from earning a degree.

Math was perhaps his greatest challenge, until he learned that he could meet his transfer requirements with two manageable statistic courses at RCC.

He enrolled in the summer of 2012.

“Because of the opportunity that Riverside City College afforded, I am able to progress now,” Jones said. “I’ve been out of prison; I have a clean and sober date of October 18, 2011. That’s the longest I’ve ever been sober in my life.”

Alongside his daughter, Jones attributes his sobriety to education, which provided him an outlet for the emotional pain previously muted by drugs and alcohol.

“School is the best therapy in the world, better than doctors and psychiatrists and psychologists and social workers,” he said. “It’s here that I find out about myself.”

With the freedom found in the classroom, Jones challenged himself to move forward, to build a foundation for a new life, spending time with his daughter on the weekends.

“If you want something bad enough, you can get it,” he said. “You can overcome mental health, you can overcome addiction.”

Through his personal interaction with CPS and the subsequent education he received, Jones decided to study social work in hopes of one day helping others who have had to walk the road he has traversed.

“I’ll have the education, I’ll have the life experience, to help other individuals like myself,” he said. “People who come from a certain walk of life or a certain socioeconomic class have to remain in touch with where they came from.”

With light spilling over the horizon in the form of academic advancement and increasing stability, Jones knows all too well that he will never truly leave the darkness over his shoulder.

“I don’t ever want to forget being homeless and bridges and shopping carts.”