By Timothy Lewis

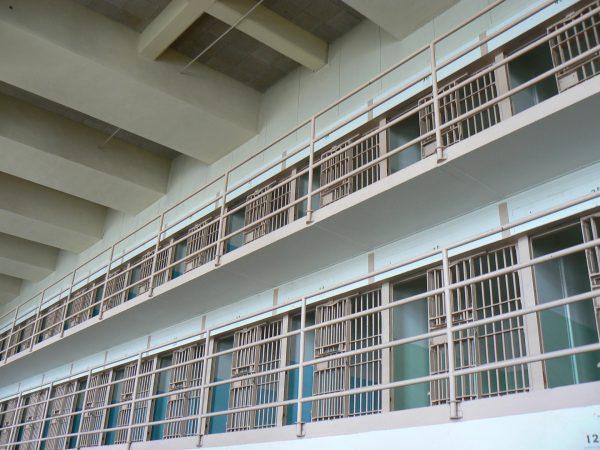

People of all backgrounds have captured the narrative of police brutality on video, but what is overlooked is the mistreatment of incarcerated individuals in the criminal justice system.

The Riverside chapter of the NAACP held a prison reform town hall April 21 in partnership with Riverside Justice Table and other local and state-ran activist organizations. They invited members of the public and recently incarcerated people to speak openly about their experiences in prison and what they believe needs to be done within the criminal justice system regarding prison reform.

The panel’s speakers varied from men and women from all walks of life. Their collective stories illustrated a picture of a complex and exploitative system that has affected countless numbers of incarcerated and detained individuals.

Panelist Diane Cardea said that her time in prison made her feel “degraded as a human being.” It made her want to change her life around, which she is now doing. Cardea is returning to school and moving to get her charges expunged from her record. She said that “people should know that even though you are in prison you are still a human being.”

Terrance Stewart, community engagement manager and founding member of the Riverside All of Us or None chapter, opened by educating the audience on the prison industrial complex system, which he called the new form of slavery. He then shared his own experience serving in prison.

A study from Freedom United showed that the United States’ public and private prison and immigration detention industry has long benefited from exploitative and profitable forced labor programs. Initiatives like the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP) incentivize private companies with government contracts with an 80% pay reduction for prisoners — meaning prisoners work nearly for free.

Economic gain has made prisons and detention centers maintain a high capacity of inmates and detainees.

Toya Vicks spoke briefly about her time working in forced labor programs in prison, from working for 5 cents an hour in “the yard” to eventually moving up to making $100 a month working in the laundry room, cleaning fellow inmates’ soiled clothes. To get such a position was an uphill battle that once achieved “was liberating,” she said.

“Even though I wasn’t getting paid they were still taking me for child support,” Vicks said. “I worked very hard to get that point, but I got there. To be able to send anything to my children was an amazing feeling.”

Stewart spoke briefly about the long-term ramifications he still faces today despite being a free, rehabilitated and functioning member of society. A few of the obstacles he listed include finding housing and job opportunities, as well as family reunification.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime shows how life outside of prison for former detainees is often tricky, as little to no job prospects are available to convicts. Many are subjected to socio-economic exclusion, beginning the cycle of poverty and repeated offenses.

Stewart noted how much the consequences of past actions can haunt a person and their loved ones long-term. He said it is one of the main reasons he got involved in fighting for prison reform.

A common theme in many speakers’ stories was the idealization of how inhumane and degrading the treatment and living conditions were behind bars. All the recently incarcerated people also emphasized that they are still people — parents, children and siblings — who deserve proper treatment despite their mistakes in life.

Prisoners are also subjected to unsanitary conditions. Overcrowding has made prisons vectors for disease and illness, with most inmates eventually being released back into the public, affecting the surrounding community.

Many on the panel were still working to rebuild their lives years after serving their sentences. Despite setbacks and challenges, these people have come together to help themselves and help the community in which they live.

Panelist Michael Griggs, who is earning a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice, believes it is the duty of those with first-hand experiences in unjust prison systems to speak out and mobilize others to change an outdated and discriminatory system.

“Those closest to the issue are also those closest to the solution,” Griggs said.