By Jennipher Vasquez

This story is the second part of a series about the history of Dodger Stadium. Read the first part here.

Members of Buried Under the Blue, an organization created by descendants of the displaced residents from the land Dodger Stadium sits on, are seeking justice and reparations for what they and their families went through 62 years ago.

The local narrative

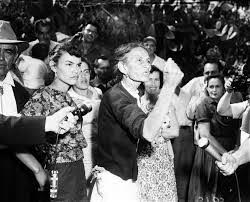

Residents of “Chavez Ravine” were presented with offers to sell their property to begin building public housing, and those who didn’t sell were violently evicted in 1959 when the city of Los Angeles finalized a deal to build Dodger Stadium.

Local officials and the media offered many reasons for the eventual displacement.

Vincent Montalvo, Buried Under the Blue co-founder, said the Los Angeles housing crisis was the start of what caused the displacements that May. Frank Wilkinson, Housing Authority official, presented the idea of turning the land into public housing units that would be named Elysian Park Heights, which the residents of these three communities disagreed with.

“We were in a housing crisis back then too. L.A. has been in a housing crisis for decades,” Montalvo said. “It seems like every time they have a housing crisis it’s a reason to take away indigenous people’s land.”

He spoke about how the Arechiga family, Buried Under the Blue co-founder Melissa Arechiga’s family, was portrayed for demanding that they be paid a fair price for their home.

The media portrayed the family as aggressive, implying they should not be allowed the right to ask for more money for their assets because the city was offering a “fair value.”

“That’s your investment, that’s the inheritance you’re going to leave your children,” Montalvo said. “They weren’t being unreasonable to the deal, they never said they wouldn’t have sold, but they didn’t want to leave. Their objective was not to leave but they did want a fair price.”

Most families in the communities were being targeted with scare tactics to force them to sell their homes. Of those tactics, community members were told that if they didn’t sell and leave, their homes would be condemned.

Montalvo relates these scare tactics to landlords in current times that unreasonably threaten tenants with calling law enforcement and facing evictions.

The homeowners of Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop were also promised that they would be granted a 2700-acre park by the Dodgers, which was never built because the Dodger corporation had the deal thrown out in court and kept that piece of land.

He and Melissa Arechiga spoke of what reparations would look like to them and their families, even though their homes have already been destroyed.

“When you look at the law, if you have in your possession stolen property, the law then and the law today makes you take that land back and give it to its rightful heirs,” Montalvo said. “It doesn’t matter who took the land, the principle purpose is that it was stolen.”

Arechiga said in an interview with historian and activist Citlalli Citalmina Anahuac, that the first step in achieving any reparations would be public acknowledgment of what they and their families have gone through.

“One of the things that we would like is a public apology from the city and County of Los Angeles, as well as the Dodgers’ corporation,” Arechiga said. “To acknowledge the wrong that they did to us and in the violent way they took the land from us, and inflicted trauma not just in our families but also the inherited trauma that a lot of us would inherit generations down.”

She also said she’d like to see three community centers erected and named after Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop to serve as locations for those affected by the displacements to come together and support one another in honor of what the communities had once hoped their futures would look like.

Activist, city commissioner and former regional field director for Bernie Sanders, Edin Enamorado, protested alongside three others at Dodger Stadium in September to bring awareness to the displaced communities.

“It’s sad that it took this for a lot of folks to know the true history,” Enamorado said in an interview with Anahuac. “The families of these three communities have been doing this for the past 60 years, it’s just sad that it took this drastic measure for folks to be reminded and for some folks to catch wind of it for the first time ever and we’re going to continue the work and never stop believing.”