The fight for California’s great lake

The fight for California’s great lake

A RIVERSIDE CITY COLLEGE VIEWPOINTS PRODUCTION

The Salton Sea’s murky water reflects the haze and clouds above. It is California’s largest lake. In recent years, many have come to believe that it is a source of adverse health effects in surrounding communities. (Leo Cabral |Viewpoints)

Story by Erik Galicia

Endless Tilapia bones and barnacle shells that vaguely resemble teeth blanket the shores of California’s greatest lake as a blanket of haze hovers above in the desert sky.

Even miles away from its beaches, the sulfuric odor that periodically emanates from the lake — a stench resembling the smell of rotten eggs — is inescapable.

The State Water Resources Control Board urged visitors to stay out of the murky, gray waters back in April when a dog died after taking a swim. The toxic algal bloom that killed the dog is just one of many problems the lake and its surrounding communities are facing.

The Salton Sea spans 30 miles from north to south and 10 miles from east to west. It sits on the border of Riverside and Imperial Counties in one of California’s most impoverished and neglected regions.

It has been shrinking for decades. Respiratory illness and chronic nosebleeds are rampant in the area, and concerned parents have connected the health issues to the toxic dust exposed as the water level drops.

But as post-apocalyptic as the Salton Sea might seem to outsiders, there is a proud and vibrant community living there — and they are not taking the issue lying down.

A potential paradise

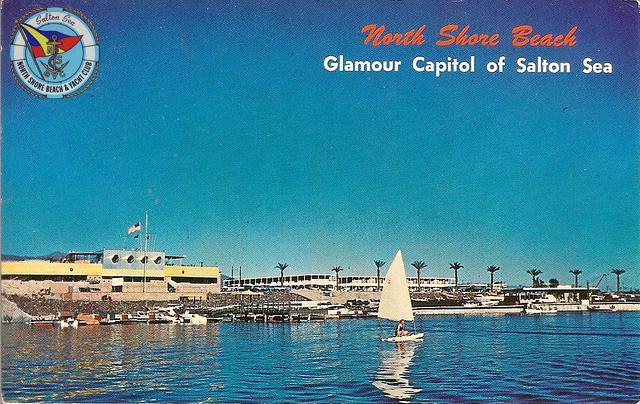

Speedboats, yacht clubs and Frank Sinatra were all the rage at the Salton Sea in the ’50s and ’60s.

“All the stars were there,” Indio resident Linda Beal said. “Desi and Lucy, The Rat Pack, The Beach Boys performed there.”

After its use as a World War II military training base, the construction of the North Shore Yacht Club and the attraction of the Salton Sea State Park brought the desert resort great potential for development.

Aside from Hollywood stars frequenting the Salton Sea, Beal said boats and families lined the shores.

“They brought people here and wined and dined them,” she said. “People bought land. Bars and restaurants were started. It was the place valley people could go to fish and waterski.”

Beal, 75, grew up on a date ranch in Indian Wells. She and her father Ben Beal, who died four and a half years ago, would spend their time on the water when she was a child.

“We used to have a lot of fun,” she said. “One Fourth of July, we stayed after dark and watched the reflections of the fireworks in the water. It was beautiful.”

There were numerous plans to construct streets and golf courses in the area, but flooding in the ’70s and ’80s washed out some of the lake’s boat launch areas. Beal believes the numerous financial recessions that followed and the uncertainty of the waters caused developers to abandon their plans.

“It wasn’t stable,” she said. “The sea came up and went down. The rise and fall was rough on resorts.”

Remnants of the once-bustling boat launches remain as ruins, which Beal said are becoming more and more visible every time she heads out to the beach.

She worked as a volunteer at the Salton Sea History Museum in 2013, the only year it was open. But even then, with the lake’s problems already growing, Beal said fascination with the sea remained.

“I’m still hopeful,” she said. “It’s still a special place for a lot of people. I still see families enjoying the beautiful sunsets. It’s still worth saving.”

The metro areas take the Colorado River

Water levels have fluctuated at the Salton Sea for thousands of years.

According to Cal State San Bernardino historian Michael Karp, Lake Cahuilla, the sea’s predecessor, was dried up by 1600.

Construction planned by engineers Charles Rockwood and George Chaffey on the Alamo Canal from the Colorado River to the Imperial Valley was complete by 1901. Farming boomed in the area.

But silt buildup caused the water reaching farmers to diminish a few years later. Rockwood went for the quickest fix possible for the silt problem: cutting a new intake on the Colorado River below the Alamo Canal intake without headgates to control the water flow.

“The Colorado River had a major flood,” Karp said. “It tears a 60-foot gap in the new canal. Another flood follows. This is where the Salton Sea comes into being.”

According to V. Manuel Perez, the Riverside County supervisor who represents the Coachella Valley, the current drying began with the 2003 Quantification Settlement Agreement, a contract between six different entities.

“Water was taken from the Colorado River … (and) transferred to other areas, like San Diego (and Los Angeles) for their water needs,” Perez said.

The agreement stated that the state would help forge a path toward the restoration of the Salton Sea.

“Unfortunately, that has not happened,” Perez said.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVeLxjaXa7A

William Porter, a UC Riverside atmospheric physicist, explains three possible scenarios for the future of the Salton Sea outlined in a report by the university’s task force studying the lake. He also explains other possible solutions and how another looming issue could impact the lake’s future. (Production by Leo Cabral | Viewpoints)

Karp said the agreement included a restoration plan, but the 2008 Great Recession depleted funds for the lake and nothing got off the ground.

It was 14 years between the agreement’s passing and the formation of the Salton Sea Authority in 2017. An increasing amount of the lake’s toxic “playa” dust was exposed during that time.

The toxic nature of this dust results from an accumulation that spans at least 100 years.

“We have to go back to the early 1900s, when DDT was something that was very common in pesticides that were used for agriculture,” Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI) community coordinator Christian Rodriguez said. “The Salton Sea was getting all that runoff for a long time.”

Rodriguez immigrated from Mexico when he was 6 years old and spent much of his youth living in the Coachella Valley. His parents were migrant farmworkers who followed grape harvests throughout the state before settling near the lake, where they joined the hospitality workforce while getting their education.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the surrounding Salton Sea communities are predominantly low-income, rural Latinx people, and they face a multitude of socioeconomic barriers.

“My community is the hardest working community,” Mecca native Sahara Huazano said. “I didn’t know I was poor. I thought that, as a child in the summer, everybody got to go work out in the fields or with their parents. I never thought that summertime was used for vacation.”

Huazano is the director of programs for Alianza, an alliance of non-governmental organizations combating the lake’s health effects as part of a social justice coalition that also includes KDI. Both of the organizers noted the stark difference between the Eastern Coachella Valley and the affluent Palm Springs area just minutes west on Interstate 10.

“There’s a huge dichotomy between living in the west end and living in the east end,” Rodriguez said. “It’s very easy for you to be driving down Monroe (Street) in Indio and then, all of a sudden, you come to Avenue 52 — agriculture, no more sidewalks, no more light posts.”

Imperial Valley farm runoff is now the main source of water flowing into the lake. Studies indicate the toxic chemicals sink to the bottom of the sea, but as the water dissipates faster than it replenishes, the chemicals are exposed in the growing playa.

According to William Porter, a UC Riverside atmospheric physicist who models wind patterns around the lake, winds from the west carry the dust into the Imperial Valley through most of the year. Winds from the east carry the playa dust into the Eastern Coachella Valley seasonally.

Census data shows the Coachella Valley and Imperial County are at 7.1% and 10.4% above the state’s average poverty level, respectively. According to the California Department of Education, these two areas hold the state’s highest rates of English learners in public schools.

These are the communities bearing the brunt of the Salton Sea’s decline.

Piecing together the puzzle

Mecca resident Maria “Conchita” Pozar’s daughters, ages 11 and 4, have frequent nosebleeds.

“We’ve taken our children to the doctors and they say it’s because the kids pick their noses or because they have allergies,” she said. “Yes, children pick their noses. But that shouldn’t result in such frequent nosebleeds.”

Pozar has noticed nasal congestion is often a sign her daughters will soon experience a nosebleed. So she takes preventative measures by keeping them from touching their noses. No matter what she does, though, Pozar said her daughters continue to experience the bleeding.

The collaborative social justice work in the area revealed to organizers that there were entire streets of children who go through the same thing.

“All the time, randomly throughout the year,” Rodriguez said. “Nobody knew what was going on. Then we started realizing that compared to other counties and other places in California, this area had extremely high numbers of asthma cases.”

According to David Lo, director of the Bridging Regional Ecology, Aerosolized Toxins and Health Effects Center at UCR, childhood asthma rates in the area are about three times higher than in the rest of the state. Community members have told researchers they believe the health impacts in the area are a direct result of the Salton Sea.

Lo is leading an interdisciplinary research project aiming to determine if that connection exists. He has been testing aerosols collected from the Pacific Ocean, various areas of the inland region and the Salton Sea on mice in chambers and watching for responses in their lungs.

Initial evidence is confirming parents’ hypotheses.

“If we do exposures with Salton Sea water, we see gene expression changes that suggest there’s a low level inflammatory triggering,” he said. “Whereas if we do the same thing with Pacific Ocean water, we see no response at all.”

Preliminary findings on exposure to Salton Sea dust also show that mice are experiencing different responses to Salton Sea particulates than those from other areas.

“In that case, we’re actually seeing a much more active inflammatory response in the lungs,” he said. “We were a little bit surprised by the magnitude of that response.”

Lo said asthma is marked by hyperreactivity in the airways. While typical asthma cases are allergic, initial findings in Lo’s research show the mice are not experiencing an allergic response. This finding may be an indicator of a different disease.

It is too early to tell if children in the area are experiencing a similar reaction. Lo said the potential of a different disease poses two questions: How would such a disease be identified in the children, and how would it be treated?

His team hopes to find answers to the many questions surrounding the lake and its health impacts, including which of the possibly thousands of metals and organic compounds in the sea are causing health issues, and whether or not children’s nosebleeds are connected to what may be happening in their lungs.

“Ultimately, we want to do more clinical studies on the kids and people who’ve grown up in that area to see if we can understand what’s going on in their lungs and nasal passages,” he said.

To Porter, the UCR team’s ability to piece the Salton Sea’s impact puzzle together could lead to accelerated action on the lake.

“Right now, a lot of the folks who are doing the policy and planning are treating the emissions from the exposed areas around the Salton Sea as equivalent to external dust sources,” he said. “If we can find a significant difference in those health impacts … then it needs to be treated with more weight than just some random surface of dust emissive areas.”

“La lucha del pueblo,” the community’s fight

The pandemic was especially rough on the Eastern Coachella Valley.

Pozar said that with over three families living in some trailers and parents who did not have the luxury of staying home, COVID-19 spread quickly. Without stable internet connections in their homes, many children, including her own, were in danger of failing in school.

Although the state is in its reopening phase, she said the disparities in the area remain the same. Mobile home parks continue to deal with arsenic-contaminated drinking water, residents in trailers rely on coolers rather than air conditioning units in triple-digit heat and adequate healthcare access remains low.

For the past few years, Pozar has been working with UCR anthropologist Ann Cheney to identify the community’s health needs, and access to doctors is at the top of the list.

Pozar said emergency room service is slow at the nearest hospital in Indio, so she sometimes opts for healthcare service in Rancho Mirage. But once she finally makes contact with doctors, additional hurdles arise.

“If the doctor doesn’t speak Spanish, how am I going to communicate with him,” she asked. “I have no way of knowing if the nurse is telling him everything I need him to know. From doctors to translators, there is a great necessity.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vTEdVutSCxA

Scientists, community organizers and area residents discuss health disparities in the Eastern Coachella Valley. (Production by Angel Peña | Viewpoints)

Pozar immigrated from the small town of Ocumicho in the Mexican state of Michoacan to the Eastern Coachella Valley nearly 16 years ago because of the area’s concentration of Purepecha people, the Mexican indigenous group to which she belongs. Some of them only speak their native language, making the language barrier even more difficult to cross.

“Some of them prefer not going to the doctor,” Pozar said. “They say, ‘If I’m going to go into a clinic just to be given Tylenol and a bill of over $1,500 by a doctor who doesn’t understand me, I’d rather stay where I am.’ Although that is not good for their health, they don’t have the money to pay for those essential medical services.”

The agreement among community members, organizers and UCR researchers is that the fight the Salton Sea’s communities are in is against systemic racism. They argued that needs have been pushed to the side for years because the communities around the lake are brown and largely undocumented.

“That’s institutionalized racism,” Cheney said. “Many of those people may not be able to vote. If they were white affluent people, the government would not be brushing them (aside).”

According to Pozar, undocumented parents often send their children to doctors in Mexicali with an adult who can cross the border. Those with documentation head to Mexicali as well, where they feel more comfortable with doctors with whom they can communicate.

A series of clinics led by UCR students have organized and implemented free medical services in the area since 2019. Cheney said the end goal is not necessarily more hospitals in the area, but bringing primary and specialized care services to the community when residents are available.

“Which means weekends, evenings, well into the night,” she said. “After people are coming home from the fields and after they’re done working.”

Scientists and government agencies alike have tried to involve community committees in their work. However, work hours have kept many from participating in conversations about solving the lake’s problems.

“These meetings run from 9 a.m to 3 p.m.,” Pozar said. “They are picking grapes, limes and peppers at that time. We can’t all go because we have to work.”

Those who can speak at government meetings have been met with comments about how a particular agency “doesn’t have jurisdiction there” and “there aren’t enough studies” to validate community members’ concerns, she added.

Alianza’s community work has focused on empowering these residents so they can raise their political voices. Its Community Science Program uses air and water quality testing models to produce data that residents can use to advocate for themselves. They also teach locals about the government systems and politicians who serve them.

“It’s a lot of engraving and building up confidence and self-esteem to make them really believe that dignity is not something that is questionable,” Huazano said.

With funding from the Coachella Valley Mountains Conservancy and California State Parks, KDI is working to redesign the Salton Sea State Park in a way that aligns with plans to mitigate dust emissions and gives area residents the tools to combat the combination of disparities they face.

The state recently granted $19.25 million for the North Lake Project, which intends to control dust and restore habitat over 160 acres while providing other community benefits. Rodriguez hopes the county will look at KDI’s work on the lake’s state park and realize community members should be guiding this effort.

“Community can and should be the ones who direct the project and decide what the project should look like, and what the project should address,” he said. “It is possible when the community understands the limiting parameters.”

Life or death for California’s greatest lake

Countless ideas for the future of the Salton Sea are up in the air.

The lake’s 10-year Management Plan in effect now intends to mitigate harmful conditions with habitat construction and dust suppression on 30,000 acres, starting on the northern and southern ends and eventually around the lake’s perimeter. According to the program’s website, 750 acres of dust suppression projects were completed in 2020.

But the 10-year plan awaits a long-term strategy, which is due in 2022. This is where the question of future inflows and water importation comes into play.

UC Santa Cruz researchers just began analyzing 11 water importation proposals submitted to the state in 2018. The possibility of bringing in water from the Sea of Cortez has reached many ears.

“It would require huge amounts of engineering,” Porter said. “It would require agreements with Mexico. It raises the question about whether folks around the gulf want to have Salton Sea water that’s going to be shared back and forth. In terms of sustainability, that would be kind of a permanent fix.”

The lake’s rising salinity currently stands at about twice the amount of Pacific Ocean water, which is one of the contributing factors to fish die-offs in recent decades. But the feasibility of such a project has made it a controversial one in the eyes of many.

Pozar, like many in her community, hopes water importation from the gulf moves forward. She called on the Mexican government to abandon political disagreements and think of its people suffering the lake’s health impacts on this side of the border.

“Think of these communities and of the children who are growing up here,” she said in reference to the Mexican government. “Your countrymen are suffering these catastrophes because of bad decisions. Let the Sea of Cortez flow into the lake and restore its life.”

Porter said the short-term fix of getting more Colorado River water into the Salton Sea is hard to argue against right now.

“That’s something that I think is not controversial and would give us a little more breathing room to make sure the water levels are maintained,” he said. “We can do that now. There’s a lot of water that’s not being used. It just takes some effort and money.”

Lack of funding has been a setback for work on the lake for years. According to Perez, state support for the lake has increased under Gov. Gavin Newsom, however. The governor’s California Comeback Plan included $100 million to boost the construction of projects in the 10-year plan.

While conversations with community members were minimal in the past, Perez said those talks are ramping up, and collaboration between the entities in the Salton Sea Authority is stronger than ever.

But with government action often slow, Pozar invited the governor and all politicians involved in policymaking around the lake to visit the Salton Sea during the summer, when she said conditions tend to worsen.

“Walk the Salton Sea,” she said. “Get on a boat and go around, but come in August. Not just for one day, but for a week or a month, so you can experience the odors we are smelling and see the health of our children.”

The discovery of what could be North America’s largest lithium deposit in the southern end of the Salton Sea has raised the possibility of economic prosperity in funding the lake’s restoration. Newsom formed a commission last year to study the feasibility of lithium extraction.

Organizers reiterated that the path forward must include community voices since so much of the past work on the lake was planned without that input.

Rodriguez is cautious of saying, “let’s restore the Salton Sea.”

“It sounds to me like ‘make America great again,’” he said. “When we’re talking about solutions to the Salton Sea, you need to take the full lens of the problem. It’s not just about the water. It’s about housing, it’s about infrastructure, it’s about who lives there.”

With infrastructure in the Eastern Coachella Valley decades behind, Huazano envisions a solution that brings sidewalks, lighting and internet to the area, and makes the lake accessible for its surrounding communities.

“You can’t just bring in these projects that cost so much money and not think about a multibenefit approach,” she said. “We would have a missed opportunity if we didn’t think about the needs of the community members that live there.”

The fight for the future of the Salton Sea is a complex and multi-faceted one that may be further stressed as the looming issue of climate change progresses. Porter said it is important for humanity to stretch its long-term problem-solving muscles.

“Why should any of us care that there are people suffering that are far from us,” he asked. “This is a problem, it’s impacting people (and) it’s going to continue to impact people more and more over time. And just because I can’t see them, doesn’t mean it’s not my responsibility to help them. Today it’s the Salton Sea. Tomorrow it may be sea level rise in San Diego.”

This map highlights the distance between some of the surrounding communities and the lake.

- Red are the communities within five miles

- Orange are the communities within 10 miles

- Yellow are the communities within 20 miles

- Green are the communities within 30 miles

- Blue are the communities within 40 miles

- Gray are the state parks and recreation ares

Erik Galicia (He/Him)

Editor-In-Chief

Leo Cabral (They/Them)

Managing Editor

Cheetara Piry (She/Her)

News Editor

Angel Peña (He/Him)

Photo Editor

VIEWPOINTS

This project was supported by California Humanities through the Democracy and Informed Citizen Emerging Journalist Fellowship Program. To learn more, please visit www.calhum.org.

Any views, finding, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of California Humanities.

“Salton Sea: An Oasis in Despair”

Produced by Erik Galicia, Angel Peña, Cheetara Piry & Leo Cabral

Videography & photography by Leo Cabral and Angel Peña

Story written by Erik Galicia

Website design & interview coordination by Cheetara Piry