By Joyce Nugent

This article is part two of the series about California’s growing water crisis. Read part one here.

The Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) estimates that 2,700 wells will go dry in the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys this year. It is not a question of if, but when Southern California will face a similar fate.

California as a whole is experiencing drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, a map released every Thursday by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In a report published in September, NOAA concluded the drought in California will continue to worsen and threaten the public health and safety of residents and affect the economy and environment of the entire state.

The atmospheric river that drenched Northern California last week is not expected to improve the statewide drought crisis.

“Even with five inches of rain in Sacramento, our deficits are immense,” said Jeffrey Mount, a geologist and water expert at the PPIC. “We’re basically missing two years of ‘precip’ in this basin. It’s not a drought buster.”

According to a poll released in July by the PPIC, a non-partisan research organization in San Francisco, one in four Californians named water supply and drought as the state’s top environmental issue.

Many Californians resisted the voluntary water restrictions requested by Gov. Gavin Newsom. As the state loses time and water, residents have reduced water use by 1.8%. This is far less than the 15% recommended by the state.

A 2007 EnviroMedia survey showed that only 32% of Americans say they “definitely know” the natural source of their drinking water.

“Our research suggests Americans would do their part to save hundreds of millions of gallons of water a day if they were reminded that their drinking water originates from a natural source, such as a lake or river, before it gets to their taps,” EnviroMedia President Kevin Tuerff told WaterWorld.

According to scientists, to survive this and future droughts, we need to change how we perceive, plan and use water. They also suggest we stay informed about our water’s source, condition and availability.

California receives 75% of its rain and snow in the watersheds north of Sacramento. However, 80% of California’s water demand comes from the southern two-thirds of the state.

The California-funded State Water Project (SWP) transports water from Northern California to Southern California through 705 miles of reservoirs and canals.

The Edmonston Pumping Plant, the biggest lift of water in the world, boosts the water nearly 2,000 feet over the Tehachapi Mountains, where it splits into the east and west branches of the California Aqueduct and enters the Municipal Water District of Southern California (MWD).

Water from the west branch is stored in Pyramid Lake and Castaic Lake for distribution to Los Angeles and surrounding cities.

The east branch of the California Aqueduct delivers water to Western Riverside County. The county also extracts water from three groundwater basins: the Bunker Hill Basin in San Bernardino, the Rialto Colton Basin in Colton and the Riverside Basin.

Eastern Riverside County receives its water supplies from a mix of local groundwater and imported water purchased through the MWD, the SWP and the Colorado River Aqueduct (CRA). The CRA carries Colorado River water from Lake Havasu on the California-Arizona border to San Diego County by way of the Mojave Desert, the Coachella Valley and through the San Gorgonio Pass.

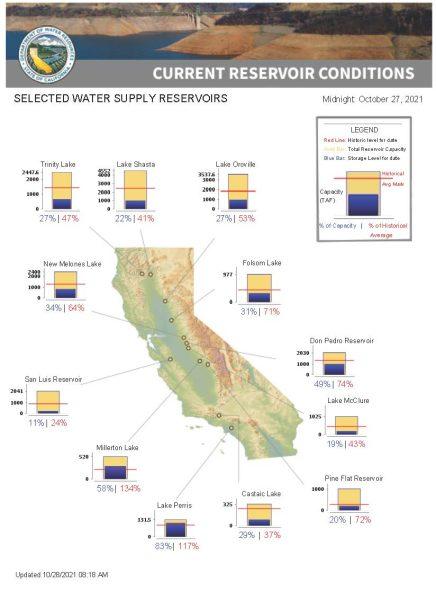

The water currently stored in the state’s reservoirs is far below normal. Lake Oroville, which holds water for municipalities as far away as San Diego, has dropped to just under half of its historical average for this time of year.

Joe Gonzalez, who lives on a beautiful two-acre parcel in Perris, is already experiencing a water shortage. He stores groundwater from a well on his property in two 2,500 gallon tanks to irrigate his citrus and magnolia trees. His well, which produced seven to eight gallons of water a minute, is now producing only four to five gallons a minute. It takes all night to refill a storage tank from the well after irrigating.

“Sometimes the tank still isn’t full in the morning,” Gonzalez said. “I have already decreased the irrigation times on my fruit trees. I am very concerned. If the drought continues, my trees will die.”

California has built the world’s most extensive interconnected water system to move water from its source in the north through the farmlands of the Central Valley to its users south of the Tehachapi Mountains.

But if not enough rain falls, or if mountain snowmelt is reduced to a dribble, the water supply to Southern California will be significantly diminished. Like the crisis in the northern part of the state, wells will go dry.

Where does freshwater come from?

The source of virtually all freshwater is precipitation from the atmosphere, in the form of mist, rain and snow. It is stored as either groundwater or surface water after it hits the earth.

Groundwater is the largest source of usable, fresh water in the world. It is stored in aquifers below the earth’s surface and is extracted using wells equipped with pumps. Pumping groundwater faster than it can be replaced leads to dry wells.

“Parts of California have already depleted their primary reserves of groundwater and are now drilling deeper – tapping into prehistoric reserves that cannot be readily replaced,” Jay Famiglietti, a water scientist from NASA, told the LA Times.

Groundwater can be artificially recharged by redirecting water through canals, infiltration basins, ponds or injecting water directly into the subsurface through injection wells.

Surface water is any body of water above ground, including streams, rivers, lakes, wetlands, reservoirs, and creeks.

Since surface water is easier to access than groundwater, it is relied on for many human uses. It is an essential source of drinking water and is used for the irrigation of farmland.

Most surface water is not drinkable without treatment.