By Paul Quick

Some are becoming increasingly aware that African Americans are wary of the recently approved vaccines that promise to restore some sense of normalcy to their and all Americans’ lives.

It is especially concerning considering how COVID-19 has ravaged our communities.

Blacks often lack access to quality health care and are more likely to work in low-end jobs that are considered “essential,” but offer less protection from exposure to the virus.

Is there such a thing as medical racism? Let’s look at the history of U.S. healthcare and the Black citizens of this country.

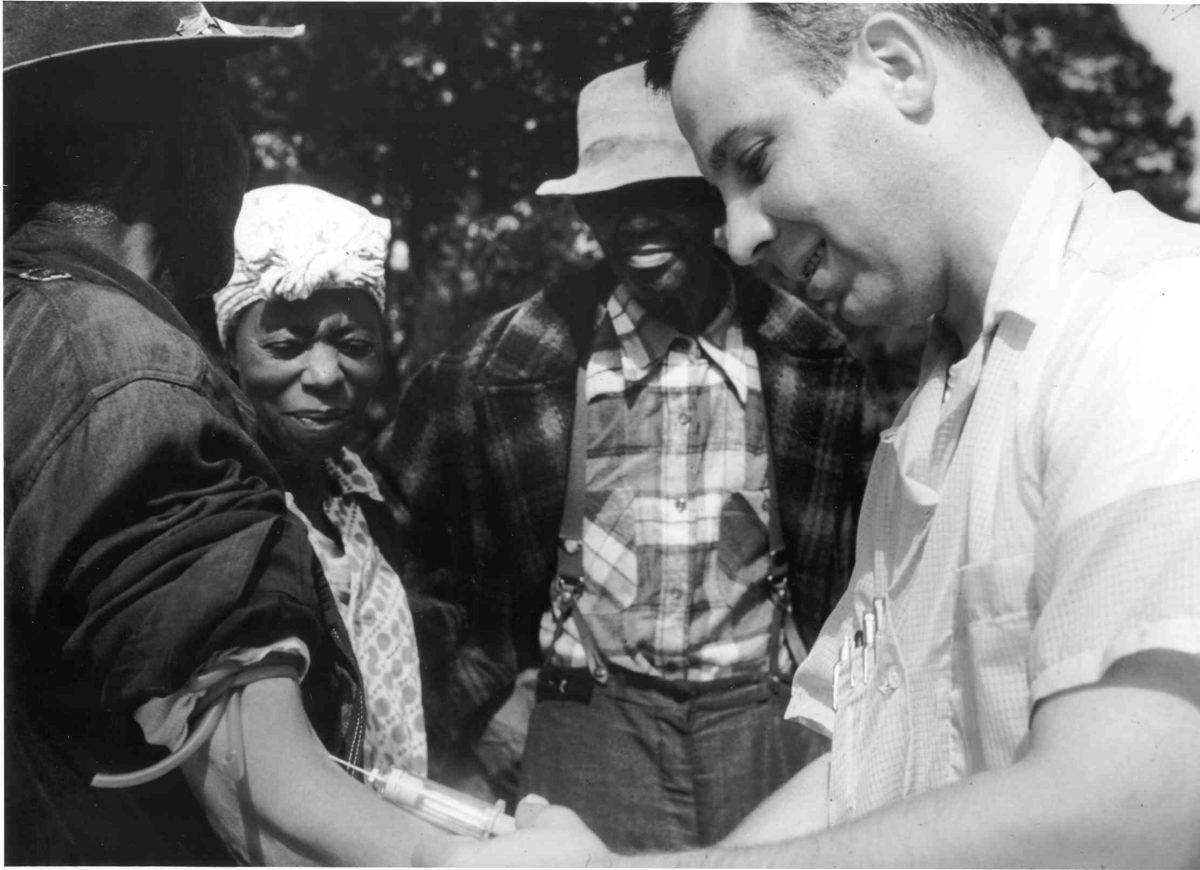

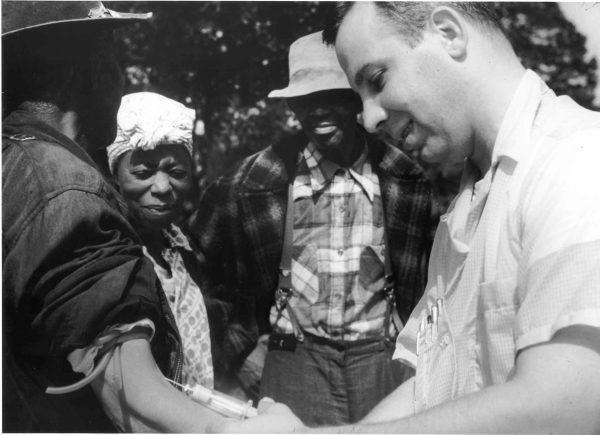

Back in 1932, the U.S. Public Health Study began an experiment called the Tuskegee Study. Black men in Mason County, Alabama who had syphilis were told they would be treated. However, the study’s actual purpose was to learn if untreated syphilis affected Black men differently than white. The entire study was based on “fake science” to determine the biological difference between Blacks and Whites.

The government never intended to provide treatment. As a result, as many as 100 men died. Hundreds of women were infected and some of the women passed the disease unto their children.

You might be thinking that someone must undoubtedly have shut down such a horrific practice after a few years. No, this inhumane “study” did not end until 1972.

Another infamous example is Dr. J. Marion Sims, the so-called father of modern gynecology, who performed extensive vaginal experiments on enslaved Black women without anesthesia.

Medical abuse of Black people even occurred after death. Medical colleges would pay enslavers and grave robbers for Black bodies so their students could study human anatomy.

In the ‘50s and ‘60s, East Baltimore residents would warn their children to be on the porch after dark to ensure their safety from being kidnapped for experiments at nearby Johns Hopkins University. When dozens of Black children went missing in Atlanta, Georgia between 1979 and 1981, some in the Black community thought the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had abducted them.

Another story well known to Black Americans is Henrietta Lacks. Lacks was a poor Black woman whose cancer cells were used by doctors and pharmaceutical companies for decades without her knowledge, permission or compensation.

Early in the 20th century, doctors forcibly sterilized women who were deemed unfit for reproduction. Of course, the majority of these women were Black. These involuntary sterilizations continued into the mid-1970s.

Although every Black American is not aware of these atrocities, they are mindful of their own challenges in navigating health care institutions.

Studies show that disparities in the medical treatment of Black patients persist to this day. They tend to be sicker and suffer higher mortality rates than their White counterparts. New Black mothers are three times more likely to die in childbirth than White mothers.

Against this backdrop of medical misconduct, we have the current administration’s earnest effort to get the message out that the vaccines are safe. Barack and Michelle Obama’s very public taking of the vaccine was undoubtedly an attempt to assuage the concerns of Black Americans. It may not be enough.

A study by the Pew Research Center reveals that only 42% of Blacks say they will take the vaccine when it becomes available to them. In comparison, 60% of Whites and Hispanics indicated they would take it immediately.

Perhaps not surprisingly, only about 50% of Whites who identify as conservative indicate they intend to get vaccinated. But that is a column for another day.

The distrust of the medical community runs deep. Another study found that one in five African Americans avoids going to the doctor for fear of medical discrimination. Many have also pointed to the rapid development and approval of the COVID-19 vaccines as a cause for concern.

It’s hard to discount these suspicions when there is so much historical data giving validity to them. Even now, there are allegations of inequity in the distribution of the vaccine.

“There has never been any period where the health of Blacks was equal to that of Whites,” Harvard historian Evelyn Hammonds told the New York Times. “Disparity is built into the system.”

One could argue that framing the distrust of COVID vaccines in everyday racism may increase underserved communities’ willingness to be vaccinated.

Public health announcements featuring Black physicians would be beneficial. It should come as no surprise that a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People study showed that Black Americans are twice as likely to trust a messenger of their ethnicity than one outside it.

It should be highlighted that a Black American woman developed the Moderna vaccine, Kizzmekia Corbett.

Perhaps the best way to remedy the atrocities of the past is to change the present. For many Black Americans, access is one thing. The willingness to take the vaccine is another.