Posted: June 2, 2015 | Written by: Aja Sanders

There is a book that he keeps on his desk, “Fire on Mount Zion – My Life and History as a Black Woman in America” written by Mabel B. Little, the same woman who raised him in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

She wasn’t his mother, nor his sister but his great aunt who in 1961 caught him trying to sneak back into the house after a party he attended the night before.

The then 19-year-old thought he made it in the world after graduating from high school the year before.

But the tables turned when Little told him that no matter how old he got, if he lived under her roof, he lived by her rules.

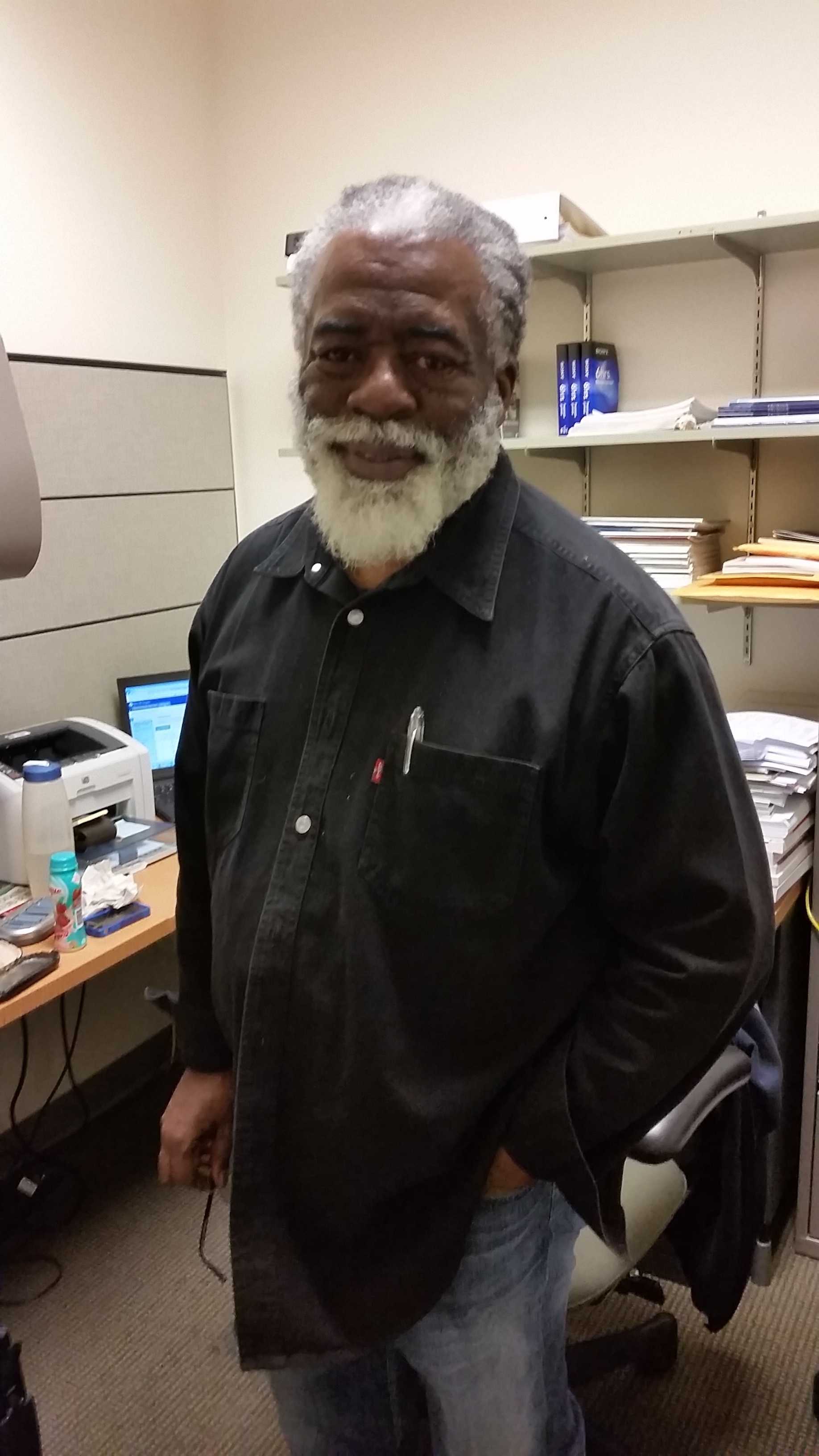

Little and two other women raised Oliver M. Thompson, Ph.D., who is a Administration of Justice professor at Riverside City College.

“I never knew my mother. I never knew my father. I was raised by my great grandmother, grandmother and this lady,” Thompson said as he referred to the book. “That’s my great aunt.”

Her photo was on the front cover.

“I was planning on being a Baptist minister, and after a year of coming back home (from college), that didn’t pan out because of family issues,” Thompson said. “‘I thought I was 19, now I’m grown’. But the rules still applied.”

In his home he had two options: work or go to college. He joined the U.S. Air Force with no hesitation.

“Looking back, I was out of my mind,” he said. “I was completely out of my mind. But, I was not afraid to step out there and do it.”

Thompson attributes his courage and eagerness to his high school experience. It prepared him not only for college, but for life.

“They prepared us to go out and be a successful American in society,” he said. “In spite of your skin color, in spite of the fact that you still had ‘white’ and ‘colored’ water fountains and you were still expected to sit at the back of the bus.”

As a young man, it never occurred to him that he would later earn his doctorate in public administration, especially after he decided to join the military after his freshman year of college.

When a man named William Broadhurst offered to pay for the remainder of his undergraduate education, Thompson turned it down because he wanted to find his own way.

He later realized that education would be his route. He became a part-time instructor in 1968 and was offered a full-time position in 1998 after he retired from law enforcement.

After a five year career in the Air Force and returning to school, he lived in Riverside and was looking for employment opportunities.

He found the Riverside Sheriff’s Department.

“I was not looking for law enforcement,” Thompson said. “The reason why I was a police officer was because I needed a job. And at that time, here in Riverside, the only thing you had was working at Kaiser in the foundry or you worked in the fields.”

Thompson admitted that he had friends in Los Angeles who looked down on him for joining law enforcement.

“They understood that I needed a job and that this was a well-paying job, but they didn’t understand what I was going to have to do to maintain and to be upwardly mobile.”

He said that he wanted to be the kind of sheriff who said yes, when it was time to say yes, and no when the time called for no. He didn’t want to be an officer who abused his authority.

Thompson reminisced on what it was like to transition to the Inglewood Police Department.

He worked in the department as a resident of Riverside and said that all of his neighbors knew who he was.

If they needed something, they could knock on his door and ask.

He was appointed Chief of Police in the department in 1992, almost a year after Rodney King was beaten by four policemen in South Central Los Angeles on the cross streets Florence and Normandie.

It was the same year that angry men and women of Los Angeles broke out in riots in fury of the video that was taped of King’s beating. Thompson said that he never felt like he was put in the path of danger, nor did he feel like he had to make decisions that he didn’t want to.

“We had a job to do. We had to protect the community the best we could,” he said. “At the time, LAPD didn’t do their job three blocks from police headquarters on Florence and Normandie.”

Thompson and the department made efforts to make things right in the community again.

He said the problem America has today with community policing is that “we haven’t learned anything in the last 23 years.”

“There are indicators of poverty, and unemployment, and lack of education, and lack of opportunities and a person really seeing that there is hope,” he said. “I have run into young people who were surprised when they turned 18, when they turned 21, when they turned 25. They never thought they would live that long and there are still those young people that are there today.”

Thompson compared the riots in Los Angeles in 1992 to the riots in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014 and in Baltimore, Maryland earlier this year.

“When you have that level of hopelessness, there is no ownership,” he said. “It doesn’t matter to them. You see, when there is no ownership then they can burn a building down because it doesn’t belong to them.”

According to Thompson, having a sense of ownership starts with the parent implementing those principles into their children at an early age.

Thompson said that it “takes a man to teach a man how to be a man” and that he still wishes that his father was in his life today.

“Those three ladies did an excellent job, but I’m wounded today, even now, not knowing who my father was,” he said. “Or being able to ask him questions, like ‘Hey dad, what would you do in a situation like this?’”

Thompson raised four children and still makes himself available to give them advice whenever he can. He wants to make sure that they don’t experience the same void that he experienced growing up.

When he looked over his life and thought about all that he had to overcome, he said that he would not go back and change anything. He never had his biological parents in his life.

He was one of only four African-Americans in the Riverside Sheriff’s Department, and he became chief of police in Inglewood during a time when some lost hope in law enforcement.

“I would not give anything for my journey,” he said. “Because that made me a man, that made me accountable, that made me responsible.”

Yet, he still does not consider himself successful. Instead, he considers himself a man who took advantage of the opportunities that were given to him.

“Momma always said,” Thompson pointed to the book, “‘don’t start something that you can’t finish,’” he laughed.

He wants all Riverside students to do the same: go after what they want and push after what they believe in.

He said that he wants young people to be aware. Aware that there is hope in times of doubt, aware of their Constitutional right to make a change and aware that everyone’s voice should and can be heard.